Reteaming for Fast Flow: A Case Study from Pirate Ship Software GmbH

Authors: Felix Krüger, Co-Founder Pirate Ship, Nina Siessegger, Independent Organizational Consultant and Coach | Team Topologies Advocate

Pirate Ship Software GmbH, facing scaling limits and excessive cognitive load, reorganized its Hamburg development team using the "Architecture for Flow" methodology (combining Wardley Mapping, Domain-Driven Design, and Team Topologies) to move from overloaded feature teams to smaller, focused units. The success was driven by a highly participatory approach involving anonymous self-selection and consent-based decisions, ensuring ownership and resulting in only minimal friction and a high degree of buy-in across the teams.

Outcomes

The structure successfully transitioned from overloaded teams to smaller, more focused units

Teams experienced reduced context switching due to clearer domain boundaries

There was increased ownership and responsibility for specific domains

The change led to simpler quarterly planning with fewer competing topics

Teams now benefit from faster decision-making

Key lessons from our re-teaming experience

Invest time in analysis. Pirate Ship used the Architecture for Flow approach — combining EventStorming and Wardley Mapping — to define clear bounded contexts. This domain analysis proved more effective than organizational assumptions.

Involve people in the change. Participation leads to better structures and stronger ownership.

Evolve, don’t big-bang. An evolutionary approach, like cell division, helps teams grow without losing what they know.

Strike before cognitive load hits maximum. Restructuring while teams still have mental capacity works infinitely better than firefighting mode.

Make it repeatable. Each iteration strengthens the organization’s ability to change, making future re-teaming easier, faster, and less concerning.

How Pirate Ship Successfully Reorganized from 3 Overloaded Teams to 6 Focused Units

Pirate Ship, one of the leading US shipping platforms, needed to reorganize their Hamburg-based development teams to accommodate growth from 20 to 30 developers. The team used the Architecture for Flow approach developed by Susanne Kaiser (a former CTO, independent consultant, and one of the Team Topologies Valued Practitioners) - a combination of Wardley Mapping, Domain-Driven Design, and Team Topologies - to restructure from three overloaded teams into smaller, more focused units.

The process involved three phases: domain exploration through Wardley Mapping and EventStorming workshops, team "cell division" using self-selection and consent-based decisions, and establishing platform teams for shared components. Teams actively participated in designing their new structure within the boundaries set by the leadership team, rather than having changes imposed from above.

The reorganization resulted in teams with clearer domain focus, reduced cognitive load, and simpler quarterly planning. While some domain overlaps remain due to the legacy monolith architecture, the approach created a sustainable pattern for ongoing organizational evolution.

Why Structures Hit Their Limits at 25+ Developers

Pirate Ship was founded in 2014 and is transforming the way businesses handle eCommerce shipping. With their free, user-friendly platform, customers gain access to the lowest UPS® and USPS® rates available — with no fees, markups, or hidden costs. Today Pirate Ship is one of the leading shipping platforms in the US. The company operates from two locations: headquarters in the USA (customer support, marketing, finance, partner management) and the German entity Pirate Ship Software GmbH in Hamburg, with around 45 employees today.

The company grew significantly starting in 2020/2021. Until then, the Hamburg development team had worked as a single unit with typical startup characteristics: minimal structure, high autonomy, and everyone working on everything. The first team split occurred in 2021, with an infrastructure team added in 2022.

By 2023, further growth was planned with at least 10 additional developers to be integrated in the next 12 months. As the company grew, the informal startup structures that once worked started to show their limits. It became clear that a more scalable setup was needed to support further growth and evolving responsibilities. Since then and in addition to the reorganization of teams an Engineering Manager role has been introduced and the product management team has been growing.

What Happened When Teams Reached Capacity Limits and Domain Boundaries Became Too Large

By this time, Pirate Ship had three cross-functional feature teams and one infrastructure team working on a monolithic architecture that had grown steadily over the years of rapid changes and fast client growth. Each team was responsible for multiple topics — some of them only loosely defined, others not owned by any team at all. The result was overlapping responsibilities and a lack of clear ownership for key parts of the system.

The teams were juggling too many complex topics at once, with unclear boundaries and constant coordination overhead. WIP was high, context switching was a daily struggle, and cognitive load kept increasing. Shared components often depended on individual developers, creating fragile knowledge silos that made the system harder to maintain.

As the company grew, the existing problems became unsustainable. Development bottlenecks significantly slowed down delivery. The core issue wasn’t the lack of capability — it was that the domains themselves were simply too large and too intertwined. Teams struggled to cultivate genuine ownership or a shared understanding within such broad scopes. And with the company preparing to hire additional developers, the limitations of the existing setup became even clearer. Scaling the old model would only have amplified its problems — more people, increased complexity, and even less clarity.

That realization became the true trigger for change. Instead of just fitting new people into an overloaded system, Pirate Ship decided to rethink its team design — aiming for a structure that could grow sustainably while preserving the collaboration, autonomy, and agility that had defined the company’s culture from the start.

The teams were organized in three cross-functional feature teams. They were able to deliver features relatively independent but they were responsible for multiple domains that were not optimally split and juggling too many competing priorities.

Enabling Growth While Preserving Culture and Effectiveness

The goals were clear. Pirate Ship wanted to integrate 10 new developers and set the teams up for further growth. They aimed for teams with a maximum of 7 members. They’ve made the experience in the past that in larger teams it was harder to foster a culture of teamwork and informal subteams have been formed as a result. The teams should have clearly defined areas of ownership and responsibility. The aim was also to reduce cognitive load through more focused domains.

At the same time, the leadership wanted to make sure that the spirit of collaboration and agility stayed alive throughout the change.

The idea wasn’t to run one big restructuring project and be done with it. The aim was to design a setup that could evolve as the company grew over years—an organization that could keep adapting without losing what defines them.

How Teams Designed Their Own New Structure

In order to address past learnings and challenges the Pirate Ship founders brought in the independent consultants Susanne Kaiser and Nina Siesssegger to accompany their journey.

To address common concerns about splitting up familiar teams, we made the process deliberately participatory. There were initial hesitations—especially around disrupting trusted working relationships and team cohesion. By including team members in every step of the design process and emphasizing transparency, choice, and psychological safety, we were able to build confidence and reduce concerns. The self-selection step in particular helped people feel a sense of agency and ownership in the reorganization.

An important learning from previous team decisions was also that the lack of an in depth domain analysis had created ongoing coordination challenges between the teams.

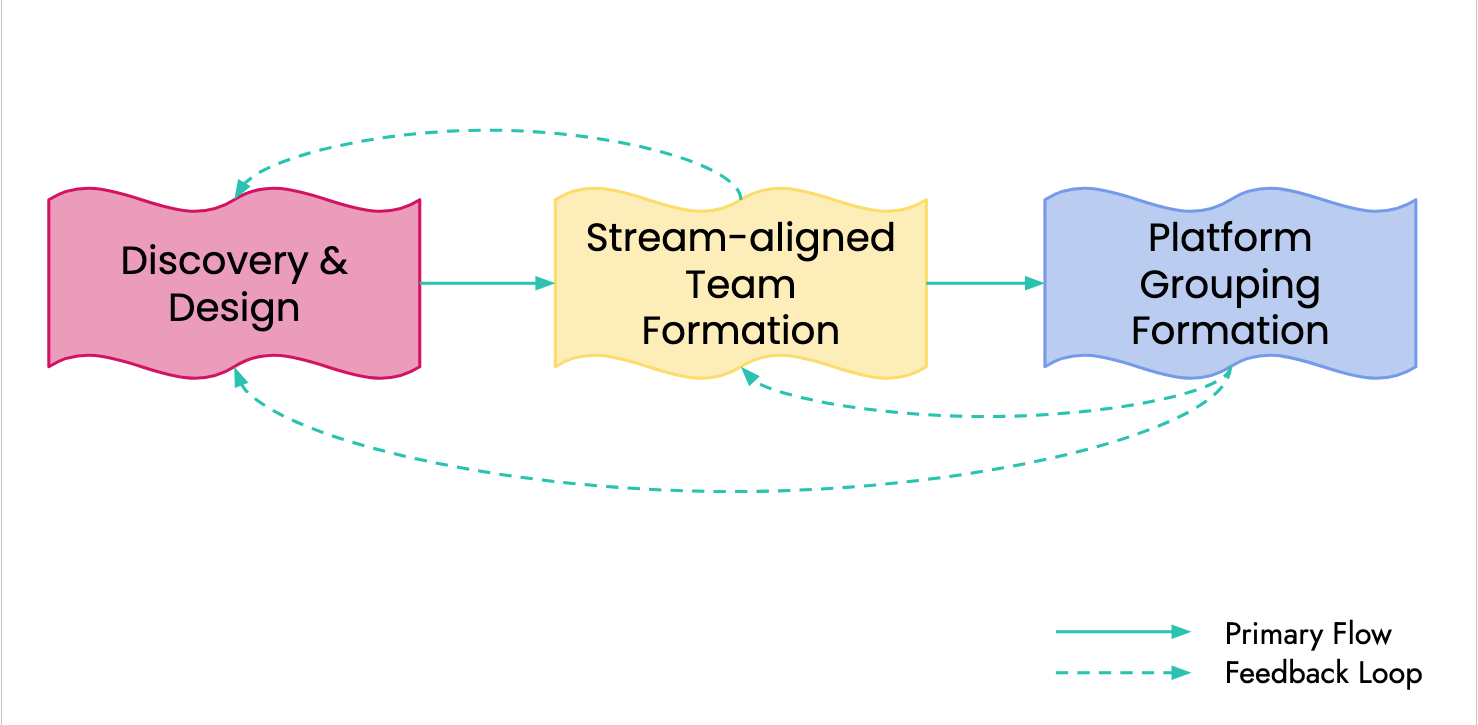

After a joint analysis of the situation we organized the work into three phases: Discovery and Design; Stream-Aligned Team Formation; and Platform Grouping Formation. However, this process was not always straightforward. We learned along the way, and sometimes what we learned later made us revisit earlier steps.

We used a cell division approach, letting teams grow organically from existing ones. This preserved crucial domain knowledge and reduced disruption. Throughout each of the phases the teams actively participated in collaborative workshops.

The process of reteaming was organized in three phases: Discovery and Design; Stream-Aligned Team Formation; and Platform Grouping Formation.

Discovery & Design: What Domain Analysis Revealed

We started with a workshop series on Wardley Mapping, Domain-Driven Design, and Team Topologies. The workshops served to train teams in these methods and analyze the business domain.

EventStorming sessions were central to this phase. Teams collaboratively mapped business processes by identifying domain events on large boards (conducted via Miro). Rather than producing final answers, this created multiple perspectives on possible bounded contexts and their groupings.

Stream-aligned Team Formation: Cell division

Two teams entered the cell division phase based on clear criteria: both had grown beyond optimal size, reached critical workload levels, and aligned with product strategy for continued growth.

We developed a 2-day workshop format that worked both remotely and in-person:

Hopes & Fears: Open discussion of expectations and concerns

Domain Division: CTO presented initial proposal based on Phase 1 findings, followed by discussion and consent-based adaptation

Skill Mapping: Identified required capabilities and assessed existing vs. needed competencies

Framework Clarification: Discussed hiring plans, team size limits, and organizational expectations

Self-Selection: Team members chose their preferred teams anonymously

Refining the Self-Selection Result: The initial distribution wasn’t a perfect fit — and that was expected. We reviewed the team setup together, checking whether the mix of skills and experience would actually work. Based on this, we iterated on the setup until the group could reach a consent-based decision. Throughout, we kept both individual preferences and company goals in mind.

Next Steps: Defined concrete actions and timeline

Teams chose different implementation timelines based on their specific situations.

Platform team formation: why platform teams became necessary

After three months, a retrospective identified both successes (more focus, clearer responsibilities) and challenges (legacy architecture misalignment, unclear shared component ownership).

This led to workshops with nearly 20 participants to design platform team solutions. The process included:

Inventory of shared components and current responsibilities

Analysis of pain points and dependencies

Assessment of stream-aligned team needs

Define potential candidates for platforms

Agreement on the responsibilities of the platform team

Transition planning for setting up the new platform team

Hiring and kicking-off the new platform team is still ongoing as of today.

The new team design

The resulting team design was following Team Topologies concepts, with 5 smaller stream aligned teams and 2 platform teams. Domains had been scoped out better, so that each team had a better defined and smaller scope.

Each stream-aligned team now owned a clearly defined domain with well-understood boundaries and responsibilities. The teams also owned a much smaller scope, which enabled them to actually take ownership and made it easier to define a shared team mission and foster teamwork. The result was a structure that reflected both the business domains and the flow of work across the system — making ownership clearer and collaboration smoother.

Applying Architecture for Flow and Team Topologies in Practice

When Pirate Ship started redesigning its team setup, the goal wasn’t to change reporting lines or management structures: the teams were already self-organized. What mattered was creating clearer boundaries and reducing friction in collaboration.

Using the Architecture for Flow approach, stream-aligned teams became the foundation. Each team’s scope now reflected a distinct business or product domain, with boundaries shaped by the outcomes they were responsible for. The bounded contexts that had emerged during the earlier domain analysis naturally turned into team boundaries, helping everyone see where their work started and ended.

Once those new domains were clearer, another challenge surfaced: several shared components didn’t fit neatly into the new structure. The idea of platform groupings turned out to be a helpful lens. It suggested creating dedicated groups that provide internal services to other teams. One existing team already worked this way — they handled the cloud infrastructure and effectively acted as a platform for the rest. Extending that idea to include other shared components felt like a natural next step. It helped bridge the gap between classic DevOps practices and the everyday needs of product-focused teams, ensuring that the platform functioned as an enabler, not a bottleneck.

The three interaction modes from Team Topologies — Collaboration, X-as-a-Service, and Facilitating — gave the organization a shared language to describe how teams work together. They helped teams see that these interactions aren’t something that “just happens,” but something that can be intentionally designed. This understanding allowed them to stay autonomous while still building the right kind of connections when needed.

Team Topologies overall gave us a common language about team design and reinforced our vision of a cross-functional team design with end-top-end responsibilities and to pursue the goal of teams being able to deliver value independently of each other. The background of Team Topologies helped to address concerns that were brought up by team members favoring the organization in functional teams and to resolve confusions around how to do DevOps in a multi-team setup with monolithic architecture.

The concept of Cognitive Load also proved invaluable. It gave teams the words to express what many had been feeling for a long time: being stretched too thin. It helped the organization talk about workload more concretely and design teams that could focus — not just survive. Because the entire process followed an evolutionary path rather than a big-bang restructure, the transition felt more organic. The “cell division” approach allowed the company to grow step by step, with each new team forming from what already worked well.

Unexpected Implementation Problems

Even with a solid framework and clear intentions, implementation came with its share of challenges — many of which are still ongoing today.

One of the biggest hurdles is the code itself. The legacy monolith still doesn’t fully reflect the newly defined domain boundaries. Refactoring it is a continuous effort that has to be balanced with everyday business priorities. The teams constantly face the question: how much time do we invest in cleaning up the foundation while customer problems are waiting to be solved?

Knowledge transfer has also proven to be more complex and time-consuming than expected, especially in domains where only a few engineers had deep expertise. While teams actively support each other, full handovers take time. Some knowledge simply can’t be transferred overnight. It has to grow through collaboration and shared experience.

Finding the right balance between participation and decision speed was another learning curve. The organization had committed to a participatory approach, but involving everyone in major decisions sometimes slowed things down. Techniques like consent-based decision-making and well-prepared proposals helped keep discussions productive while maintaining transparency and shared ownership.

Forming the new platform team turned out to be one of the toughest parts. Unlike the stream-aligned teams, it couldn’t simply emerge through “cell division.” Instead, we tried to staff it by sourcing engineers from existing teams — but no one volunteered at first. Moving engineers internally proved harder than expected, and external hiring is still in progress.

Results After Six Months

About six months after the reorganization, the changes were clearly visible in everyday work. Collaboration within the new, smaller teams improved noticeably. People worked more closely together, and the sub-teams that had once handled separate topics inside the larger units disappeared entirely. Each team now had a well-defined domain, and with that came a stronger sense of ownership and responsibility.

Quarterly planning, which used to be a complex balancing act, became much simpler. Teams had fewer competing priorities and could focus on what mattered most. Decisions were made faster, without endless coordination loops, and the constant context switching that had once drained energy was greatly reduced.

Not everything fell into place right away. Some domain overlaps remained because the codebase hadn’t yet caught up with the new structure. The legacy monolith still tied parts of the system together in ways that didn’t perfectly reflect the organizational boundaries. Knowledge transfer was also an ongoing effort, even though teams actively supported each other to close those gaps.

At the same time, the organization learned a lot. Each subsequent reteaming became easier, and one team even started proactively suggesting new divisions or the creation of new teams whenever they spotted opportunities to optimize. The approach developed into a repeatable pattern for continuous evolution—an organizational muscle that keeps growing stronger with each iteration.

The biggest insight? Don’t wait until teams start to struggle under their own size. Reorganize while there’s still capacity, energy, and curiosity to shape change together and keep changes small and fast.

Next steps: applying Team Topologies at scale

Request a keynote talk to inspire your teams and kickstart a transformation initiative

Order 50 or more copies Team Topologies Second Edition now in bulk - with free worldwide shipping

Buy an Enterprise Content License with access to a huge library of official Team Topologies workshop and training materials to catalyse large-scale transformation

Get an online consultation on Team Topologies with one of the co-authors of the book

If you missed the Team Topologies Second Edition marathon launch event on 25 September 2025, here are the resources