When DORA metrics meet governance in banking - Expert View

The “Expert View” articles from Team Topologies feature perspectives from industry experts in different sectors. These views explore topics adjacent to Team Topologies and/or situations where Team Topologies approaches are highly beneficial.

Key takeaways

Manual governance processes conflict with fast DevOps practices, causing bureaucracy, slowing delivery, and increasing risk due to reliance on extensive paperwork and human-in-the-loop approvals.

External approval functions like Change Advisory Boards (CABs) are largely ineffective assurance mechanisms, yet organizations with formal external approval processes were found to be 2.6 times more likely to be low performers.

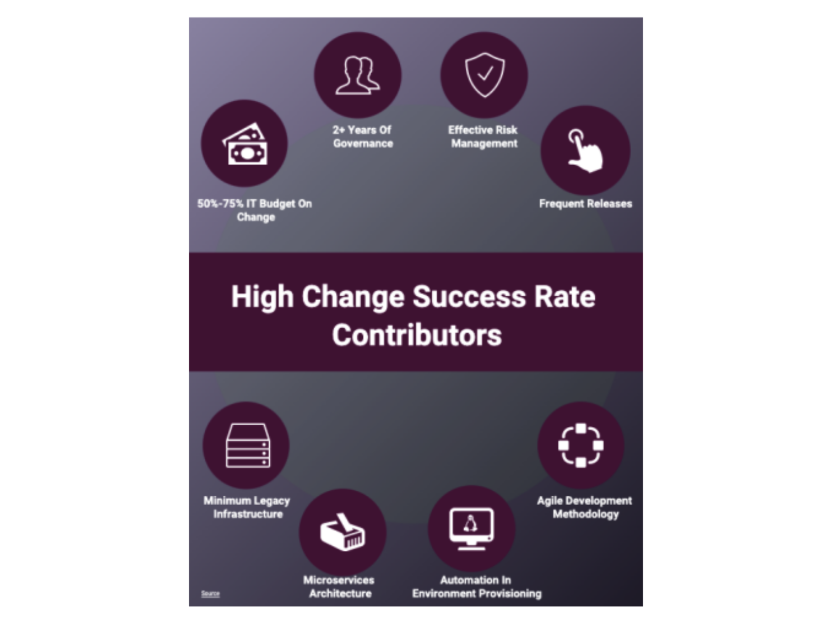

DevOps practices, including frequent releases, automation in environment provisioning, and modern architecture, are key contributors to high change success rates, confirming they are better solutions for managing real-world risks.

DORA recommends replacing slow, formal approvals with agile, automated change control, primarily using peer review-based approval and leveraging continuous testing and integration for early detection of bad changes.

Successful DORA implementation requires domain expertise to interpret perceptual results, aligning those results with internal strategy (e.g., focusing on trunk-based development), and building enablement groups to coach teams on specific improvement mechanics

Introduction

What happens when you’re a large bank that has spent a decade investing in DevOps, but still uses IT and change advisory board meetings to approve changes for release to production?

This is the conflict playing out in large banks today - software delivery is increasingly automated and fast, but governance is still manual and slow. Developers can ship changes quickly, but those changes run into a wall of bureaucracy before they can be delivered to customers.

Banks are legally required to implement change management, but the processes they use haven’t been able to keep pace with the speed of their DevOps. Also, it’s an open secret that these processes are not only slow and wasteful, but also really ineffective at mitigating against risk.

But, what if we could control our risks without slowing everything down? What if we could automate the change management function to align with our DevOps? Research tells us that this is the way, and innovators in the banking industry are already pressing ahead.

The Old Ways of Controlling Risks are Ineffective and Inefficient

Mike Long, Kosli

Software teams in highly regulated sectors like banking, but also in industries like healthcare, and aerospace, use rigorous governance frameworks for software development and delivery. This is how they meet their regulatory requirements and - in theory! - protect themselves and their customers against risk.

These frameworks often involve enforced risk controls such as code review processes, security checks, change approval workflows, audit reporting, and deployment gates. But the vast majority of this activity is done manually by humans in the loop, in contrast to the highly automated DevOps world that exists upstream.

Take the example below from an internal developer survey done at Morgan Stanley, where the bank tried to quantify the cost of deploying a single change into production. What you’ll notice is that these steps can significantly slow development velocity.

“One engineer documented all of the things they had to do to get a single line of code into production. It required 3 different Jiras, a change ticket, and 81 individual steps just to get the paperwork created and approved. ”

And this is for a single change! Imagine the cost at scale when we’re dealing with millions of changes…

These requirements were designed for traditional, slower release cycles. But as the industry increasingly adopts devops and cloud practices, the process that works for a quarterly release just doesn’t fit when you want to deploy continuously.

The Failures of Traditional Governance

It’s not just an issue of speed. Using manual processes to manage risks doesn’t make things safer, it makes them more dangerous. Instead of reducing risk they increase risk.

By slowing down every change with documentation and approvals, you open up the risk of human error. Again, thinking about scale, how likely is it that human beings can ensure the security of millions of changes going through manual gates? It’s just not realistic.

Furthermore, when it comes time to audit, you have to manually gather evidence and prove conformance. But, because the governance process is driven by paperwork, audits inevitably uncover compliance gaps and control failures leading to more paperwork in the form of remediation.

This all adds up to a doom-loop where engineering finds it really hard to meet the delivery demands of the business.

What does the regulator say?

The ironic thing about this situation is that even the regulator is frustrated by the status quo.

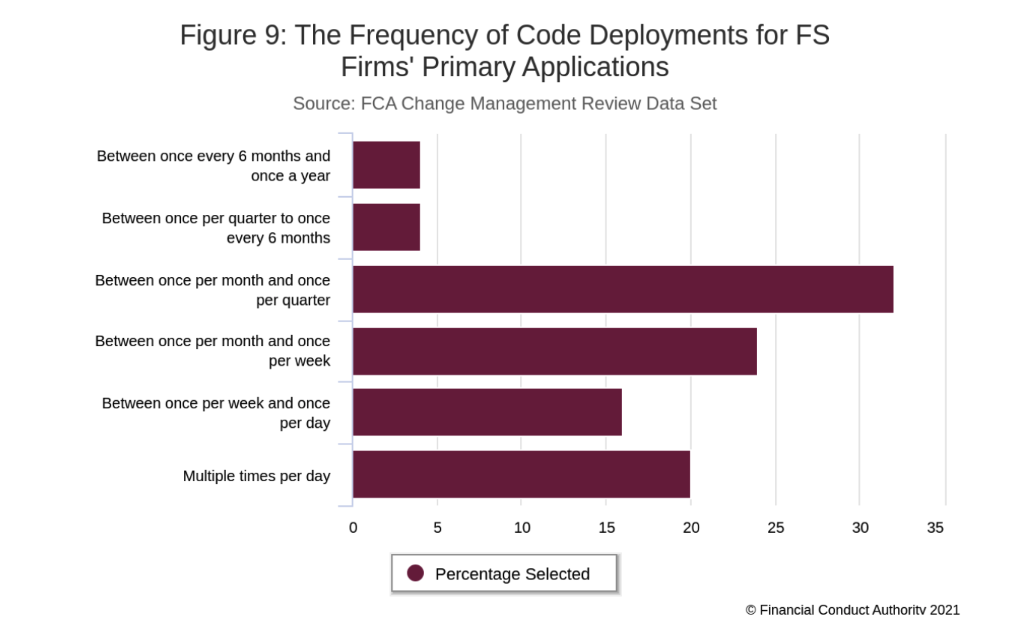

The Financial Conduct Authority (the UK’s regulatory body) published a report analyzing data from over 1 million production changes. Their goal was to understand what works and what doesn’t work in the land of regulated change.

What they found was not at all surprising to DevOps practitioners working day to day at the coal face. However, it was directly opposite to what many people assumed was true about typical industry practices in financial services.

What the FCA found was that the key contributors to success include frequent releases, modern architecture, automated infrastructure and agile development methodologies. In other words, DevOps practices are shown to correlate with successful changes.

Ok, but how close is the industry to achieving these goals? Well, when they looked at the deployment frequency for core systems, they found that the majority of firms were at a very low performance level.

One reason for this is an area where they had significant findings - the Change Advisory Board (CAB). The CAB is a process where an external function acts as a gatekeeper for technology changes, where teams have to submit documentation and attend meetings in order to get changes to production. The CAB is a very common function in regulated software delivery.

What they found was that the CAB as a control function was largely ineffective:

“One of the key assurance controls firms used when implementing major changes was the Change Advisory Board (CAB). However, we found that CABs approved over 90% of the major changes they reviewed, and in some firms the CAB had not rejected a single change during 2019. This raises questions over the effectiveness of CABs as an assurance mechanism.”

And they’re not the only people to have recognized how ineffective CABs are. In Accelerate, Dr. Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble, and Gene Kim came to an even starker conclusion way back in 2018:

“We found that external approvals were negatively correlated with lead time, deployment frequency, and restore time, and had no correlation with change fail rate. In short, approval by an external body (such as a change manager or CAB) simply doesn’t work to increase the stability of production systems, measured by the time to restore service and change fail rate. However, it certainly slows things down. It is, in fact, worse than having no change approval process at all.”

Prior to publishing Accelerate, the authors had spent three years measuring the efficacy of DevOps through the DevOps Research Assessment (DORA) project they started in 2015.

Acquired by Google in 2018, DORA continues to provide excellent guidance on software delivery best practices based on extensive research. It’s at this point I’ll tag in Nathen Harvey, DORA Lead and Developer Advocate at Google Cloud, to explain what the latest research has to say:

What does the DORA research say?

Nathen Harvey, Google

DORA is a long running research program that seeks to understand the capabilities that drive software delivery and operations performance.

DORA provides valuable insights into software delivery governance, emphasizing that heavyweight change approval processes actually hinder performance and offering alternative approaches to streamline processes, improve auditability, and effectively address governance and compliance concerns.

DORA's research consistently shows that formal change management processes that require approval from an external body, such as a Change Advisory Board (CAB) or a senior manager, have a negative impact on software delivery performance. Organizations with such formal approval processes were found to be 2.6 times more likely to be low performers (see Accelerate State of DevOps 2019)

Contrary to the belief that these heavyweight processes reduce risk, DORA found no evidence that a more formal approval process is associated with lower change failure rates.

To streamline change approval and improve software delivery performance, DORA suggests a shift towards more agile and automated approaches:

Peer review-based approval: Change approvals are best implemented through peer review during the development process. This approach can also satisfy requirements for segregation of duties, with reviews, comments, and approvals captured in the team's development platform.

Leverage automation for early detection and correction: Supplement peer reviews with automation to detect, prevent, and correct bad changes early in the software delivery lifecycle. Techniques such as continuous testing, continuous integration, and comprehensive monitoring and observability provide early and automated detection, visibility, and fast feedback.

Treat development platform as a product: The development platform should be designed to make it easy for developers to get fast feedback on the impact of their changes across various aspects, including security, performance, stability, and defects.

Prioritize early problem detection: Focus on finding problems as soon as possible after changes are committed and performing ongoing analysis to detect and flag high-risk changes for additional scrutiny.

End-to-End process optimization: Analyze the entire change process end-to-end, identify bottlenecks, and experiment with ways to shift validations into the development platform.

Clear communication of processes: Simply doing a better job of communicating the existing change approval process and helping teams navigate it efficiently has a positive impact on software delivery performance. When teams clearly understand the process, they are more confident in getting changes approved in a timely manner.

Ok, but you might be wondering what implementation looks like in practice? At Deutsche Bank, Toby Weston shares how they used DORA to establish a baseline for the organization:

What is working in practice now?

Toby Weston, Deutsche Bank

At Deutsche Bank, implementing the DORA survey across a global, heterogeneous engineering organization surfaced a number of challenges — some expected, others less so.

Survey Mechanics in a Complex Org

Running a perceptual survey like DORA in a large enterprise isn’t just about sending out a link. We had to carefully cluster participants into groups that were both statistically meaningful and operationally actionable. Too broad, and the insights become vague. Too narrow, and you lose signal. Add to that the sheer diversity of tooling, methodologies, and maturity levels across teams, and it became clear that interpreting results would require more than just dashboards—it would require domain expertise.

Compounding this was the pace mismatch between our internal cadence and the evolution of the DORA framework itself. By the time we concluded our survey cycle, Google had already moved on—retiring the “Elite” category and shifting their clustering model. That made it harder to message progress internally. Senior leadership naturally aspired to “Elite,” but that benchmark was already outdated. The subtlety of these shifts—and their implications—required careful framing. We produced an SME White Paper, reviewed with Google to help position our case.

Interpreting Perception with Precision

Because DORA is a perceptual measure, we were cautious about how maturity might skew responses. More experienced teams might rate themselves more critically, while less mature teams might overestimate their capabilities. This made it essential to have a central group of SMEs and Enablement Engineers (inspired by Team Topologies) to help interpret the data and socialize the underlying capabilities behind the metrics.

Aligning DORA with Internal Strategy

Before running the survey, we had already identified two strategic themes through internal tooling and SME observation: the need for greater focus on automated testing, and the importance of reducing branch integration times (moving toward trunk-based development). These hypotheses were backed by static code analysis across our Git repos—similar in spirit to tools like Swarmia or BlueOptima. Encouragingly, DORA results validated these themes: ~75% of teams reported trunk-based development as a

low-capability, high-impact area. That alignment gave us the confidence to push forward with targeted initiatives.

Bridging the Capability Gap

Even with clear signals, many teams weren’t sure how to improve. Reporting low capability is one thing—knowing what to do next is another. That’s where our enablement group played a critical role: not just in interpreting the data, but in helping teams understand what “good” looks like and how to get there.

My Recommendation

Treat DORA as the start of a conversation, not the end. Build enablement into your operating model—whether that’s through coaching, playbooks, or embedded SMEs. And make sure teams know where to go for help once the results are in. Our teams accepted the advice, but we weren’t expecting them to ask for very low level (specific) advice on the mechanics of improvement.

Without instrumentation and measurements, we found DORA to be slow moving (and coarse grained - with the 4 keys), so we needed lower-level measures that we expected to affect the larger ones - hence custom tooling.

Summary

The real-world risks associated with software delivery in regulated industries has created a history of governance that is better solved with DevOps approaches. The regulator agrees, the DORA research backs this up, and it is proven to work in practice right now.

Learn more: DORA Community

About the expert authors

Nathen Harvey leads Google Cloud's DORA team, using its research to help organizations improve software delivery speed, stability, and efficiency. He focuses on enhancing developer experience and is dedicated to fostering technical communities like the DORA Community of Practice, which provides opportunities to learn and collaborate. He has co-authored several influential DORA reports and contributed to the O'Reilly book, "97 Things Every Cloud Engineer Should Know."

Toby Weston is a Developer Advocate and Distinguished Engineer at Deutsche Bank, where he drives SDLC governance towards modern, evidence‑based solutions. He focuses on improving developer experience through DORA, SPACE, and DevEx principles, helping teams deliver faster while maintaining compliance. Toby is the author of Scala for Java Developers (Apress), is a regular speaker and has written extensively on engineering practices for JavaTech and elsewhere.

Mike Long is founder and CEO at Kosli, a developer tools startup for understanding DevOps changes, and one of the tools in the curated Team Topologies Success Toolkit™. He has been delivering software in various cultures and industries for 20 years as an engineer, architect, consultant, and CTO. Based in SF, Mike volunteers in the community, and is also a trustee of the cyber dojo foundation.

The Team Topologies Success Toolkit™ is a carefully curated collection of trusted tools that work seamlessly with Team Topologies patterns and principles. These aren’t just any tools - they’re specifically designed and enhanced to bring Team Topologies concepts to life at scale.